On December 12, 1944, The Imagery of Chess opened at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York City on the 4th floor of a townhouse at 42 East 57th Street. Conceived by the Dadaist and chess master Marcel Duchamp, gallery owner Julien Levy, and Dadaist and Surrealist Max Ernst, the exhibition brought together a group of artists who were challenged with designing chessmen that differed from the traditional and formal Staunton and “French” sets used in everyday chess and tournament play.

On View: September 29, 2016 - March 12, 2017

Tasked with creating new “figures, at once more harmonious and more agreeable to the touch and to the sight,” over 30 artists, many of whom had previously exhibited with Levy, participated in the project, creating a variety of boards and sets as well as sculpture, music, paintings, and drawings. Though a few of the participating artists—Alexander Calder, Man Ray, André Breton, and the organizers were well known at the time, others such as Matta, Arshile Gorky, Robert Motherwell, and John Cage would emerge as significant figures in the second half of the 20th century.

Coinciding with the height of World War II, this playful and whimsical exhibition was celebrated at the time and received great press coverage in both mainstream media (Newsweek, Town & Country), and art and chess journals (Art Digest and Chess Review) among other publications. Strangely, the details of the show were not documented thoroughly and the exhibition had been widely ignored among art historians. No checklist was recorded, or has been found, so there is much speculation as to what each artist contributed to the show. Thanks to the work of independent curator, artist, and scholar, Larry List, working as the first guest curator at The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York, in 2005 the exhibition The Imagery of Chess Revisited was organized and an accompanying catalog published. Upon reviewing archival images, Levy’s gallery ledger, and press images, List and a network of cooperative institutions, artists, estates, and private individuals reconstructed much of the original exhibition. Bringing together many of the actual works of art and reconstructing many of the “lost” pieces, the exhibition gave new life to a forgotten unique collaboration and conflation of art and chess.

Designing Chessmen Opening Reception

September 29, 2016

Photo: Austin Fuller

With a mission to interpret the game of chess and its cultural and artistic significance, the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) is honored to celebrate the history of The Imagery of Chess and its impact on future artists and our own institution. September 2016 marks the fifth anniversary of the WCHOF’s existence in Saint Louis, Missouri. Since our opening, we have staged 10 exhibitions that merge art and chess—two of which were group shows where artists reinterpreted the game of chess and incorporated their artistic ideas into either chess sets or chess-related imagery. The inspiration to do this comes directly from the 1944 exhibition, and more specifically, the chess-related art created by Marcel Duchamp.

The WCHOF will continue to explore the myriad of creative notions of chess to enrich our viewers’ experiences with this ancient game. In 2017, the WCHOF will continue to pay homage to the original The Imagery of Chess when we ask local artists to create chess-related artwork. We look forward to this project as we continue to celebrate Saint Louis as the U.S. Capital of Chess.

—Shannon Bailey, Chief Curator, World Chess Hall of Fame

The Imagery of Chess

Origins

In the summer of 1944, New York gallerist Julien Levy and his friend the German painter and sculptor Max Ernst rented a house near Great River, Long Island, along with their respective partners American painters Muriel Streeter and Dorothea Tanning. These avid chess players were shocked that their house was not furnished with a chess set. However, seeing their problem as a creative opportunity, Ernst and Levy immediately set to work inventing their own plaster chess pieces in Ernst’s makeshift sculpture studio in the garage.

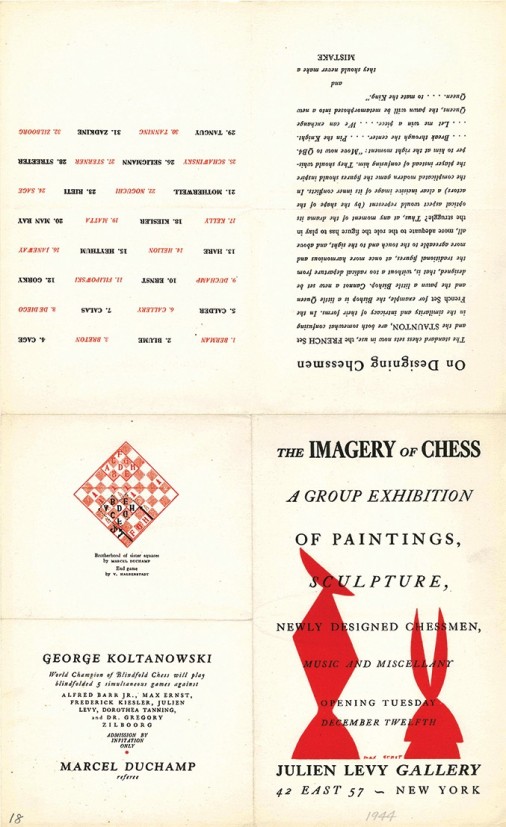

Surprised and pleased with their plaster chess creations, Levy and Ernst decided to invite everyone in their creative circle to design chess sets and chess-themed art for a winter holiday exhibition of affordable works, great and small. Levy wrote a brief manifesto “On Designing Chessmen,” advocating the replacement of the stodgy 19th-century chess set designs with new forms “...more agreeable to the touch and to the sight” ones “... more adequate to the role the figure has to play in the struggle...” whose visual “...aspect would represent...a clear incisive image of its inner conflicts...” and would “...inspire the player instead of confusing him.” Invited to help his friends organize the event, artist and chess master Marcel Duchamp rallied the chess community and designed a 4-quadrant folding announcement/brochure with Levy’s manifesto and iconic red silhouettes of the new, abstract chess pieces by Ernst. They entitled the exhibition simply The Imagery of Chess, and broadly described it as a “group exhibition of painting, sculpture, newly designed chessmen, music, and miscellany.”

Healthy Heterogeneity

Unlike other art historians or gallerists of his era, Levy had taken studio courses in painting, sculpture, photography, and filmmaking while studying at Harvard in the mid-1920s. He even took a class about Renaissance egg tempera and plaster casting techniques nicknamed the “eggs and plaster course.” Inspired by his friend Constantin Brancusi’s abstract sculptures and using Surrealist word play to suggest a starting point, Levy literally made his Chess Piece Prototypes from plaster casts of egg shells saved from his breakfasts. He preserved them in their cardboard cartons and then had a local craftsman produce his chess set prototypes larger in wood.

To Levy, Ernst, and Duchamp, creativity was not bound by medium, style, or vocation. They invited expatriate European Modernist and Surrealist painters and sculptors but also Neo-Romantics and young, scruffy, aspirant New York School artists too. Architects; scenic, graphic, and industrial designers; photographers; a ceramist; a research librarian; two music composers; two art theorists; and a famous Freudian psychiatrist rounded out their roster. Unlike the provincial American art world “boys’ club,” this show of 32 participants had eight women, seven couples, and 14 nationalities.

To avoid the boredom of like-mindedness in the show, the organizers invited people with differing attitudes toward chess. Man Ray, Alexander Calder, Xanti Schawinsky, Vittorio Rieti, Dorothea Tanning, and Muriel Streeter, among others, loved chess. Artists such as Isamu Noguchi, Kurt Seligmann, Yves Tanguy, Kay Sage, Jean Hélion, and Julio de Diego understood the game but did not really care about it. Still others, like André Breton, Nicolas Calas, and Roberto Matta were among those who openly hated the game. Surprisingly, everyone, even the disinterested and adversarial parties, contributed engaging and provocative works.

Max Ernst

Max Ernst’s earliest known chess set was a series of loosely sculpted plaster forms pictured in a photo of Plaster Chess Set, 1929. Between 1929 and 1930 these king, queen, and bishop figures were mounted together on a base and editioned as Roi, Reine et Fou, a trio which may have been included in The Imagery of Chess show. Ernst, a serious player, also prepared a framed watercolor referred to as his Strategic Value Chess Board 1 and a second version of it which served as the board of Xenia Cage’s Chess Table. He additionally offered the 16 piece plaster set of his transitional design, 1944 Plaster Chess Set Prototype, along with three complete sets of his now classic 1944 Wood Chess Set. The forms, suggestive of Easter Island and African sculptures, were initially composed from fragments of plaster casts of funnels and other kitchen utensils which Ernst then had reproduced in different combinations of hardwoods by the local craftsman Levy had found. Ernst also exhibited the plaster version of what became his most famous sculpture, The King Playing with the Queen, a large, horned Minotaur King seated at a chessboard, his right hand forward protecting his Queen while his left hand hides the beheaded torso of another Queen figure behind him.

Marcel Duchamp

Though he played a large part in organizing the show, Duchamp exhibited the smallest known work, an altered readymade object. It was a wallet-style pocket chess set held by a rubber glove pinned to the wall, with pins as center points of the chessboard grid supposedly to hold the celluloid chess piece tabs Duchamp had custom-made. The French chess master was making a visual pun referring to the chess tactic of “pinning” an opponent’s piece in a position that rendered it useless. Often referring to art as “useless,” Duchamp ironically offered the convenience of a portable chess set but rendered it useless (hence now art) by inviting the player to try to move the miniature “pinned” pieces while wearing a large clumsy rubber glove. Duchamp attempted to sell copies of his “pin-grip pocket chess board” with the help of his friend Grandmaster George Koltanowski, with whom he staged a blindfold chess event on January 6, 1945. With Duchamp as interlocutor, Koltanowski simultaneously defeated Levy, Museum of Modern Art Director Alfred Barr, Jr., artist/designer Xanti Schawinsky, composer Vittorio Rieti, painter Dorothea Tanning, and Max Ernst. Architect Frederick Kiesler forced a draw.

Designing Chessmen Opening Reception

September 29, 2016

Photo: Austin Fuller

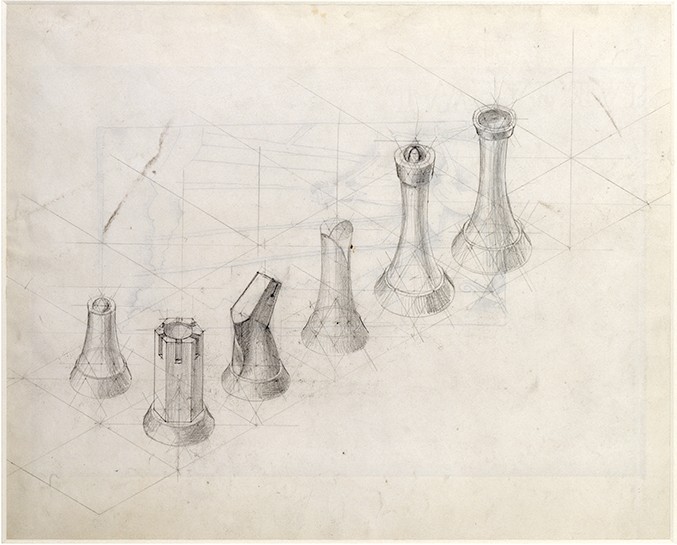

Man Ray

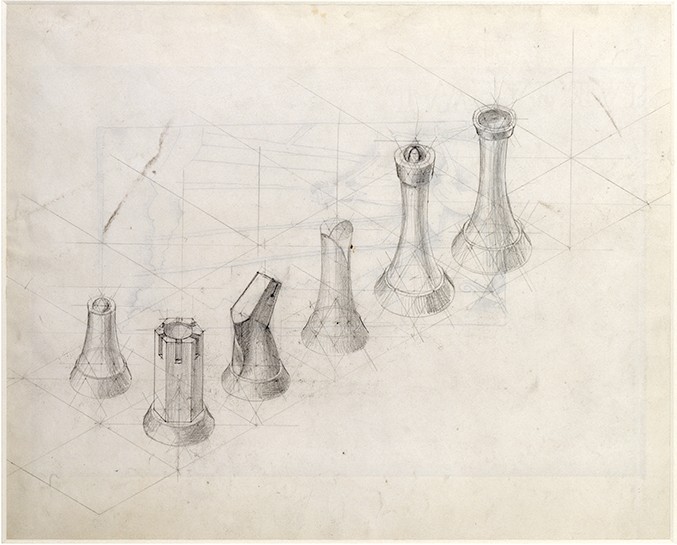

Living in self-imposed exile in Hollywood, California, from 1940 until 1951, Man Ray was an eager, though long-distance participant in the exhibition. Though this American Dadaist and Surrealist began designing chess sets as soon as he had mastered mechanical drawing in high school, as demonstrated in Recto: Perspective Study for Chess Pieces, he assembled his first actual chess set in 1920 from wooden found objects in his studio. He sent his deluxe 1926 Silver Chess Set, an enlarged version of this first 1920 wood set to The Imagery of Chess show. This 1926 set and its table design was the inspiration for his later 1962 Chess Set and Table edition. Man Ray may also have submitted an earlier 1944 version of Design for Chess Pieces drawing from which one set was ordered and produced in 1945. Unable to participate in person at the Blindfold Chess Match Duchamp planned, Man Ray may also have sent the photograph Self Portrait with Chess Set, and his chessboard painting The Knight’s Tour to represent him as a player in absentia.

One of Duchamp’s chess friends, Freudian psychiatrist Dr. Gregory Zilboorg loaned the show an early 1923 prototype of what was to become the iconic 1924 Josef Hartwig Bauhaus Chess Set. Perhaps the first chess set whose sole subject was the nature of the game of chess itself, this set visually portrayed the “... role the figure has to play in the struggle.” Derived from identical wooden blocks, the abstract shape of each piece portrayed its identity solely by indicating its direction of movement.

Milieu

Having suffered the senseless, chance privations of warfare before arriving safely in America the European artists, especially, drew closer to the game of chess. Chess was the game of war, but it was a cathartic one. It was an orderly game of skill with rules, not blind chance, determining one’s destiny. For these disenfranchised immigrant artists the opportunity to design a chess set, to create a harmonious ensemble of new forms, allowed them to imagine a new, more ideal model of society and network of relationships. Then, as now, chess offered players and artists alike a sense of community.

Scarce Materials

scarcity of good materials generated a strong psychic urge to piece together a new world from whatever could be found. Chess set prototypes and the sculptures that Ernst and David Hare exhibited were plaster originals, not bronze casts. The lack of fresh art supplies drove artists to work with found objects and salvaged materials instead. In 1942, Alexander Calder used slices of a broom handle to create his first Traveling Chess Set, then went on to use odds and ends of wooden bric-a-brac, including the sawn-off legs of his studio sofa as the rooks, to complete his Assemblage Chess Set and Board of 1944. Scarcity promoted reducing forms to their minimal limits as Yves Tanguy did with his Chess Set and Tabletop Board, first made in Paris, 1938, then again in New York in 1944. The sets he fashioned, also from broom handles, rival the Hartwig Bauhaus Chess Set for simplicity, functionality, and clarity of identity and purpose. Surrealism’s theorist André Breton and art critic Nicolas Calas took the use of scavenged found objects even further by assembling a temporary Wine Glass Set and Board from borrowed wine glasses and mirrors.

New Materials

Though wartime made the familiar materials scarce it also introduced artists to new experimental materials. Laszló Moholy-Nagy sent his protégé Richard Filipowski’s Clear Chess Set entirely from transparent surplus Plexiglas. Xanti Schawinsky used curving lengths of the plastic rod to describe artillery trajectories over a chessboard battlefield, and Isamu Noguchi used Plexiglas to fashion colored abstract silhouette-figure Chess Set pieces and the inlays on the Chess Table he made from two other new aviation grade materials, lumber core plywood and cast aluminum. Man Ray’s friend, the Czech architect and stage designer Antonín Heythum, a government advisor on civilian substitutions for strategic materials, sent a small chess set of lathe-turned and anodized aluminum, which influenced Man Ray’s post-war designs.

Tradition & Innovation

While new materials and scarcity of familiar ones sparked innovation, so too did these artists’ awareness of chess history and tradition. Levy, Duchamp, Ernst, and Man Ray all had their own chess libraries, and through copies of H.J.R. Murray’s 1913 masterwork A History of Chess, many of the other artists drew inspiration from the 14 centuries of chess history. Noguchi’s intense study of Indian culture and art led him to make his chess pieces sparkling red and green and his table black with inlaid white center-points instead of squares, to pay homage to traditional ruby and emerald chess pieces on black lacquered Indian boards with their round mother of pearl center-points. Levy’s cast plaster chess board expressed his love of both Eastern and Western stylistic traditions. A fan of Early Italian Renaissance painter Piero della Francesca’s perspective geometry, Levy inscribed a forced perspective grid into the plaster board surface but, with a nod toward the Indian board mother of pearl center-points he embedded a lustrous mother of pearl seashell in the center of each square.

Figuration & Abstraction

By the time of The Imagery of Chess show in 1944, the experiments of Surrealism, which had begun in the 1920s to build bridges between reality and dreams, had reached the boundaries between figuration and abstraction. Around this time, Chilean architect-turned-Surrealist painter Roberto Matta tutored ambitious young New York painters Robert Motherwell, Arshile Gorky, and Jackson Pollock in Surrealist collage and calligraphic automatic writing techniques. Matta promoted a new “Abstract Surrealism” to them. The picturing of chess sets and boards offered the perfect nexus of figuration and abstraction.

Chess pieces, designed as harmonious families of forms almost always read as figures, even when abstracted. However, the chess boards they were moved about on were increasingly viewed as purely geometric, gridded, totally flat, abstract spaces. They were canvases across which linear, multi-directional, non-perspectival painting gestures, like chess moves, could be made in a new type of conceptual space. The dialogues that Gorky and Motherwell had with Matta and the exposure that the New York art community had to “chess space” described in the chess board grid paintings of Man Ray, Dorothea Tanning, Max Ernst, John Cage, and Julio de Diego in The Imagery of Chess show may have contributed to the development of the at picture plane abstraction of the New York School and by extension to later forms of Minimal grid-based art.

Looking Back—Looking Forward

The Imagery of Chess exhibition of 1944 was an idea simply sparked by the absence of a chess set. Yet, it led a diverse range of creative talents to produce an incredibly rich variety of work based on the 14 centuries of chess history and culture. It gave 20th-century modernists alternative ways to think about space, form, and movement; offered a new set of abstract Modernist norms; and has encouraged the aesthetic explorations of subsequent generations of artists, designers, and architects.

—Larry List, New York, August 2016

Works Featured in the Exhibition

Cage

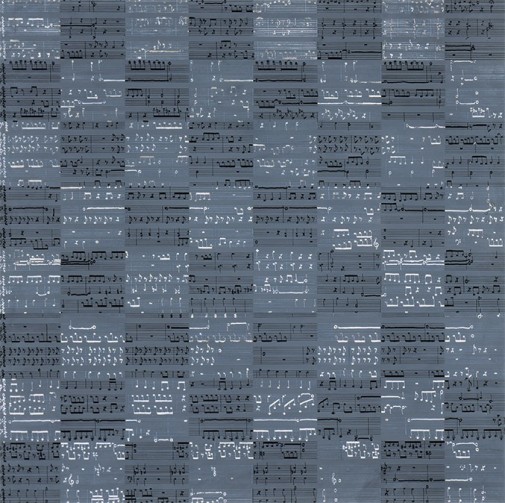

John Cage (1912-1992)

Chess Pieces, 1944

Reproduction of a painting

19 x 19 in.

Private Collection, © John Cage Trust

The experimental composer and artist John Cage was invited to participate in The Imagery of Chess by Julien Levy. The two met in 1943 when Cage purchased a Matta drawing from the gallery. Cage was also friends with Ernst and Duchamp—the other two organizers of the exhibition. Cage was never a great chess player but, by his own admission, used chess largely as a pretext to spend time with Duchamp.

Cage created a checkerboard pattern as he hand-painted a musical score in white and black ink, forming a grid. Though many artists created “playable” chessmen for the exhibition, Chess Pieces was hung on the wall like a painting, while other boards were either played directly on or glass was put on top to protect the artwork.

Calder

Alexander Calder

Chess Set, c. 1944

Wood and paint

Calder Foundation, New York. Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, NY

© 2016 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Calder premiered his invention of “mobile” sculptures at his 1932 exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery. Calder created three different chess sets (one is pictured here) and drawings around 1942–1945. His exact contributions to The Imagery of Chess are unknown.

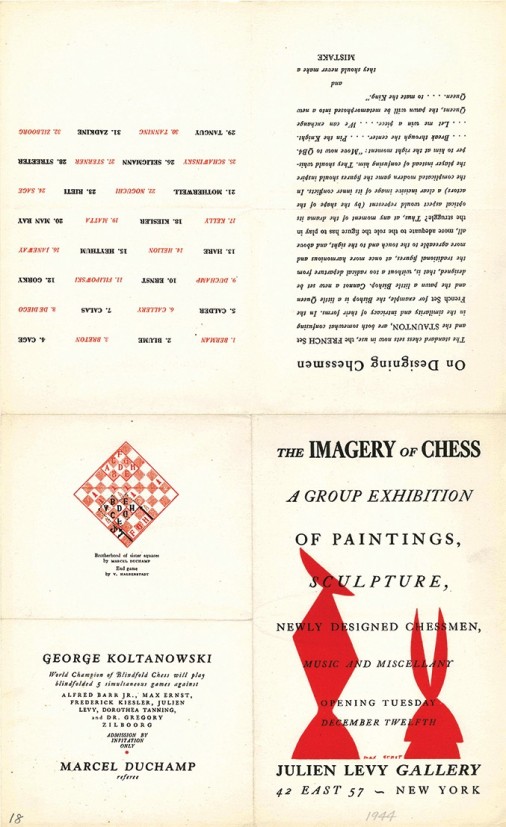

Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), French

The Imagery of Chess invitation/brochure, 1944

Red and black ink on paper

20 1 ∕8 x 14 3 ∕8 in.

Collection of the World Chess Hall of Fame

© Succession Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2016

In addition to featuring the silhouettes of two of the more striking pieces from Max Ernst’s Wood Chess Set, with the towering queen on the left and the distinctive profile of the bishop on the right, the invitation/brochure for The Imagery of Chess also includes a list of the 32 artists or pairs (same as the number of chess pieces in a set) involved in the exhibition, Duchamp’s essay titled “On Designing Chessmen,” and one of the diagrams from his endgame study. The brochure also announces the participants set to compete against the “World Champion of Blindfold Chess” George Koltanowski, who still holds the record for the most simultaneous blindfold matches at thirty-four, a feat he accomplished in 1937. The courageous seven (Ernst, Dorothea Tanning, Julien Levy, the composer Vittorio Rieti, the designer and photographer Xanti Schawinsky, former director of the Museum of Modern Art Alfred H. Barr, Jr., and the architect Frederick Kiesler) played with the various sets on display in the exhibition, with Duchamp serving as referee. All were defeated except Kiesler, who managed to draw. Three original photographs from that event are on display in this gallery.

Ernst

Designed by Max Ernst (1891-1976), German

Chess Set, Designed 1944

Stained boxwood

King size: 4 1⁄2 x 2 1∕8 in.

Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of John F. Harbeson, 1964

© 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Designed by Max Ernst (1891-1976), German

Chess Set with Board, Designed 1944

Stained boxwood

King size: 4 1⁄2 x 2 1∕8 in.

Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of John F. Harbeson, 1964

© 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Ernst’s famous chess set is a beautiful balance of hard angles and delicate curves. The design reflects contemporary trends in modernism, particularly as he blended traditional Western chess piece designs with forms derived from African, Oceanic, and Native American art.

In this set, the largest piece is actually the queen, an unusual departure from convention that may reference her importance and power in the game. The distinctive silhouettes of this piece and the bishop grace the cover of the Duchamp-designed invitation to The Imagery of Chess.

Filipowski

Richard Filipowski (1923-2008)

Chess Set, Designed 1942

Acrylic resin

King size: 3 in.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of John F. Harbeson, 1964

Image Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Filipowski, the youngest participant in The Imagery of Chess at the age of 21, exhibited an updated version of Josef Hartwig’s famed Bauhaus Chess Set from 1923. Using acrylic plastic, a brand new material at the time, the work of art was a one of the most successful pieces in the 1944 exhibition. Nearly the same height, the king and queen are differentiated by their respective shapes. The queen is essentially a cylindrical rod, whereas the square king has incised lines on the top that show the directions that the piece can move, while doubling as an approximation of a crown. The design of the remaining pieces similarly underscore their respective ranges of movement. The set was favorably reviewed by Art Digest (December 15, 1944), and was immediately purchased by the architect John F. Harbeson, one of the pre-eminent chess-set collectors of the day. Harbeson later donated it to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

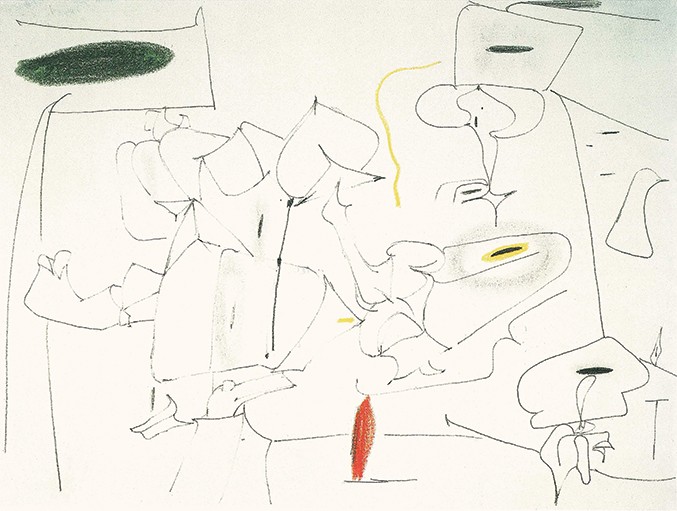

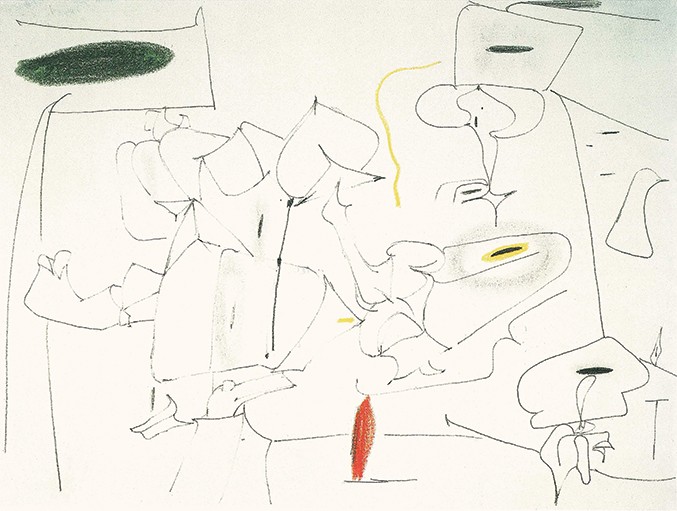

Gorky

Arshile Gorky

Untitled (Study for a Delicate Game), c. 1946

Pencil and crayon on paper

Collection of Gerald and Kathleen Peters

© 2016 The Arshile Gorky Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

After participating in The Imagery of Chess, New York abstract painter, Arshile Gorky, was given 4 subsequent solo shows at the Levy Gallery. His chess show work is unknown due to a fire that destroyed his studio in 1946. It is likely that he contributed something similar to this known work from 1946, such as Untitled (Study for a Delicate Game).

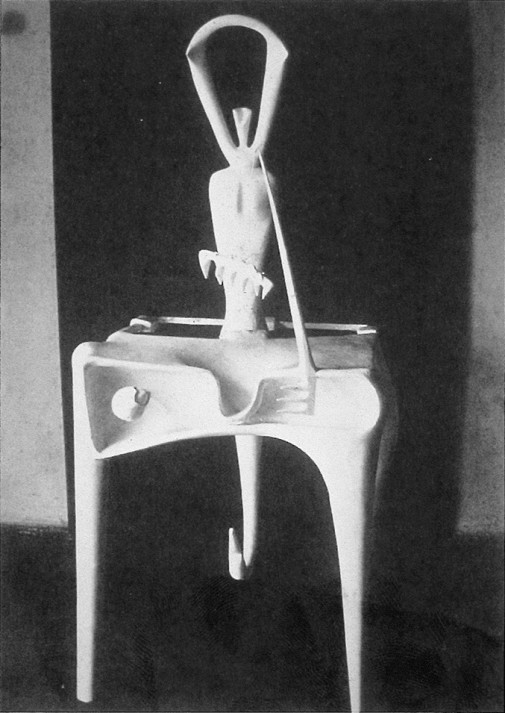

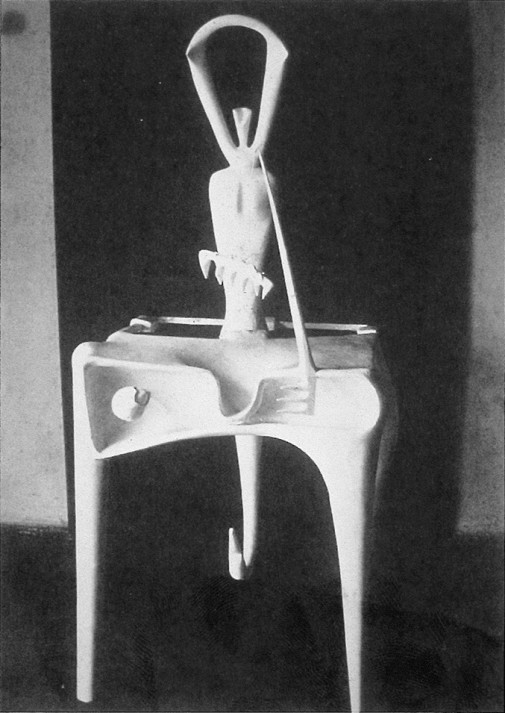

Hare

David Hare

Magician’s Game, 1944

Plaster (cast in bronze, 1946)

Plaster original shown in artist’s studio

Photograph: David Hare, c. 1944

© Estate of David Hare

The experimental photographer, editor, and Surrealist sculptor David Hare contributed one large plaster sculpture, Magician’s Game, to the 1944 exhibition that was later cast in bronze.

Hartwig

Josef Hartwig (1880-1955)

Bauhaus Chess Set Previously Owned by Walter Gropius, early 1920s

Wood pieces in original cardboard box

King size: 1 13∕16 in.

Box: 5 x 5 x 2 in.

Collection of Doug Polumbaum

© 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

The Bauhaus Chess Set is unique in this exhibition as it was not created for the show, nor is it contemporaneous with the other works in the exhibition. Rather, this set was designed two decades earlier while Hartwig was an instructor at the Bauhaus, the famed German art school that promoted a unification of art and craft. Its curriculum immersed its students in all manner of design, particularly in such traditionally marginalized media as cabinetry, metalwork, and textiles. In the cabinetry workshop, for example, students were encouraged to distill a chair down to its material essence, eliminating that which is unnecessary in order to emphasize the elegance of simplicity in design. The same aesthetic approach can be seen in Hartwig’s chess set, in which the pieces are fashioned from identical wooden cubes. The Bauhaus philosophy of maximizing utility is also evident in this set, as the pieces are distinguished from each other by being representative of their respective moves on the board. Levy’s exhibition featured an early prototype of this set loaned by the psychiatrist Dr. Gregory Zilboorg. This set was once owned by Walter Gropius, the German architect and co-founder of the Bauhaus School.

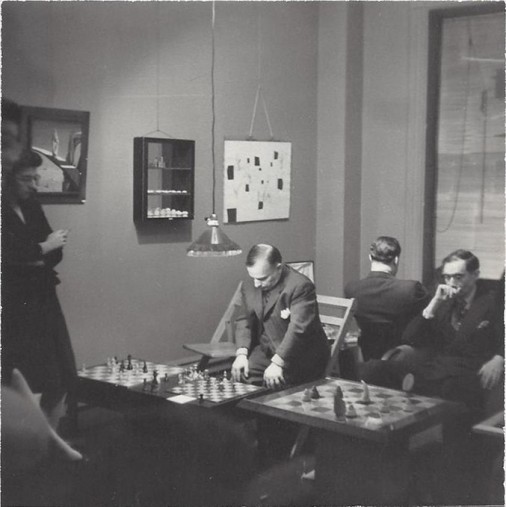

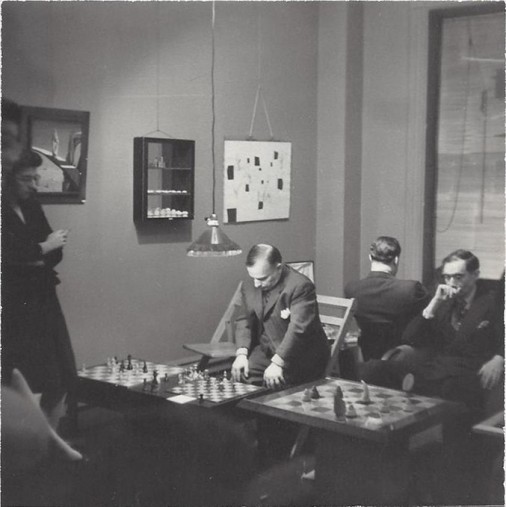

Levy

Julien Levy (1906-1981)

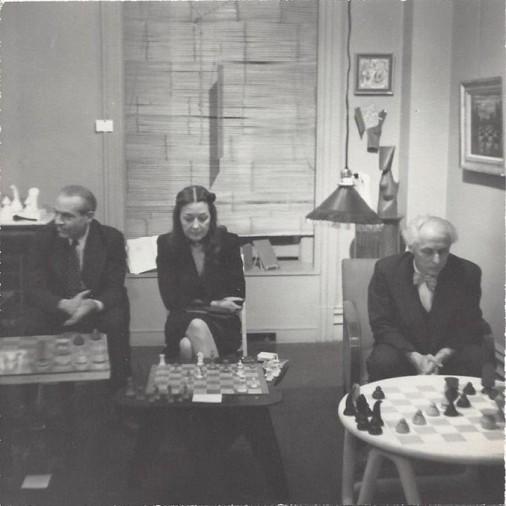

The Blindfold Chess Event, Julien Levy Gallery, January 6, 1945

Black and white photograph

4 x 4 in.

Collection of the Jean and Julien Levy Foundation for the Arts

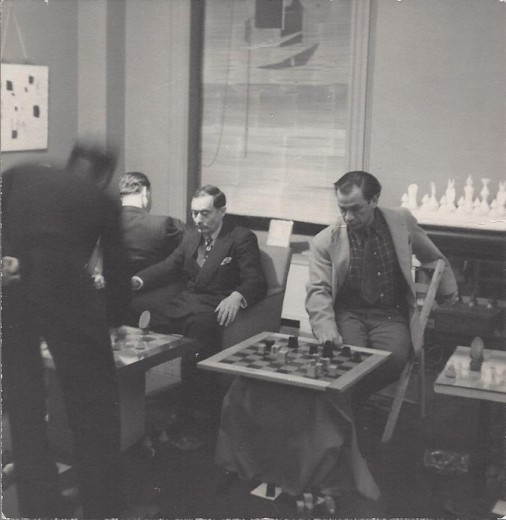

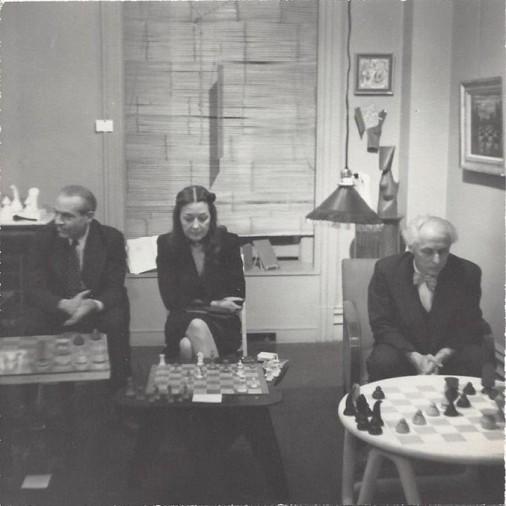

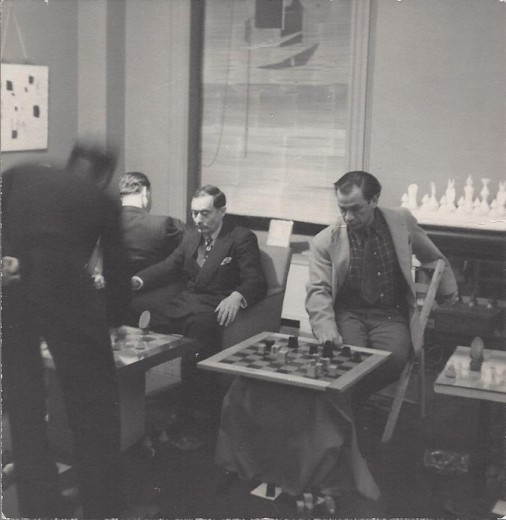

Julien Levy (1906-1981)

The Blindfold Chess Event, Julien Levy Gallery, January 6, 1945

Black and white photograph

4 x 4 in.

Collection of the Jean and Julien Levy Foundation for the Arts

Julien Levy (1906-1981)

The Blindfold Chess Event, Julien Levy Gallery, January 6, 1945

Black and white photograph

4 x 4 in.

Collection of the Jean and Julien Levy Foundation for the Arts

The invitation to The Imagery of Chess (on display in this exhibition) included an announcement for the “Blindfold Chess Event” in which:

"George Koltanowski

World Champion of Blindfold Chess

will play blindfolded 5 simultaneous

games against Alfred Barr Jr.,

Max Ernst, Frederick Kiesler,

Julien Levy, Dorothea Tanning, and

Dr. Gregory Zilboorg

Admission by invitation only

Marcel Duchamp, Referee"

1986 U.S. Chess Hall of Fame inductee, George Koltanowski (1903-2000) played all of these participants with the additions of Vittorio Rieti and Xanti Schawinsky. No chess notation is known to exist. It was said that Koltanowski defeated all with the exception of one match—a draw with Kiesler. Koltanowski held the world record for the most blindfolded simultaneous matches with 34 players until his record was surpassed in 2011.

As noted in the 2005 exhibition catalog by curator Larry List:

[First] Photo:

Frederick Kiesler (center) plays chess grandmaster George Koltanowski (with back turned) to a draw. Alfred Barr Jr. (right) contemplates his defeat on a Max Ernst 1944 Wood Chess Set on top of Ernst’s Strategic Value Chessboard 1, framed under glass. On the wall, from far left, are Kay Sage’s oil painting Near the Five Corners; a display cabinet with Julien Levy’s Plaster Chess Piece Prototypes; Carol Janeway’s ceramic Chess Set; Matta’s 6 Threats to a White Q; and, suspended in the window, one of Xenia Cage’s wood and rice paper mobiles.

[Second] Photo:

Marcel Duchamp (with back to camera) makes a move for Koltanowski (far left) versus Alfred Barr Jr. (center). Xanti Schawinsky plays using Josef Hartwig’s Bauhaus Prototype Chess Set provided by Dr. George Zilboorg. On the wall, from far left are Matta’s 6 Threats to a White Q; one of Xenia Cage’s wood and rice paper mobiles hanging in the window; and behind Xanti Schawinsky, Max Ernst’s Plaster Chess Set Prototype. Below them, near the floor, is Ernst’s bronze Roi, reine et fou (King, queen, and bishop).

[Third] Photo:

Composer Vittorio Rieti (far left) plays with a Max Ernst 1944 Wood Chess Set on top of Ernst’s Strategic Value Chessboard 2, made for (but not pictured on) Xenia Cage’s Chess Table. In the center, Dorothea Tanning plays with a Staunton chess set and chessboard on top of Isamu Noguchi’s Chess Table. At right, Max Ernst plays with the third of his chess sets in use on an unidentified table. Open, on the windowsill behind Tanning is a book, probably Duchamp’s and Vitaly Halberstadt’s Opposition and Sister Squares Are Reconciled (1932). In the window is one of Xenia Cage’s wood and rice-paper mobiles. In the corner, at the top of the wall, hangs an unidentified painting. Below it is Duchamp’s Pocket Chess Set with Rubber Glove. On the right wall hangs Leon Kelly’s painting The Plateau of Chess.

Julien Levy (1906-1981), American

Chess Piece Prototypes (45) with Their Exhibition Copy Egg Carton, 1944

Plaster and cardboard

King size: 2 in. Box: 1 15∕16 x 11 11∕16 x 5 7∕16

Philadelphia Museum of Art: Purchased with the Bloomfield Moore Fund, 2007

Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

In the summer of 1944, Levy, along with his wife Muriel Streeter, Max Ernst, and his girlfriend Dorothea Tanning, rented a house on the South Fork of Long Island. Upon discovering there was no chess set in the house, the group of artists decided to create their own. This immediate need became the inspiration for the exhibition The Imagery of Chess.

Shown here are the plaster prototypes made from the discarded shells from Levy’s own soft-boiled eggs from breakfast. Levy’s “Humpty-Dumpty” pieces were designed to fit nicely in the sand, making the set portable. The original prototype is exhibited with a replica of the egg carton and box. The carton and box still exist and are in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Julien Levy (1906-1981), American

Chess Set: Board and Thirty Pieces, 1944

Chess Pieces: stained and painted oak

Chessboard: cast reinforced plaster with incised lines, seashells

King size: 2 3∕16 in.

Board: 1 1⁄4 x 24 x 24 in.

Philadelphia Museum of Art: Purchased with the Bloomfield Moore Fund, 2007

Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

After Levy designed the prototype for his chess set, he created a plaster chessboard to accompany the finished set. Perhaps inspired by the seaside location where the set was conceived, Levy embedded seashells in the chessboard to cradle to the egg-shaped pieces.

The chess set is slightly larger than the prototype and is carved out of oak, which was painted or stained to represent the opposing sides.

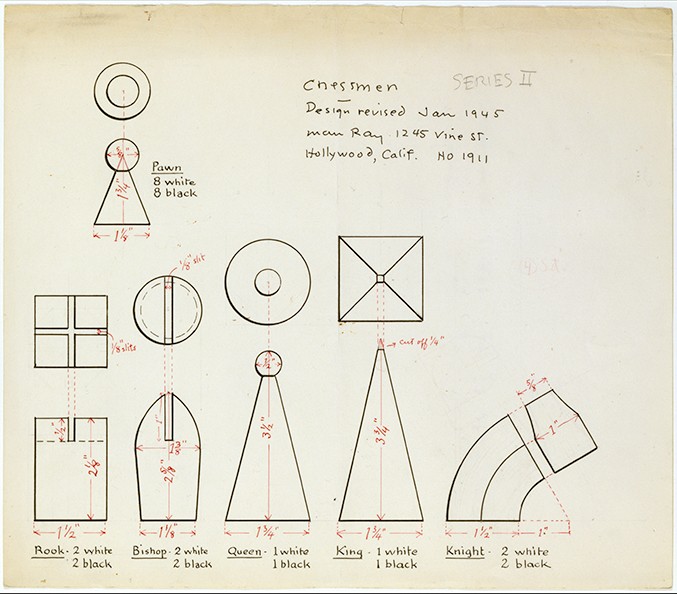

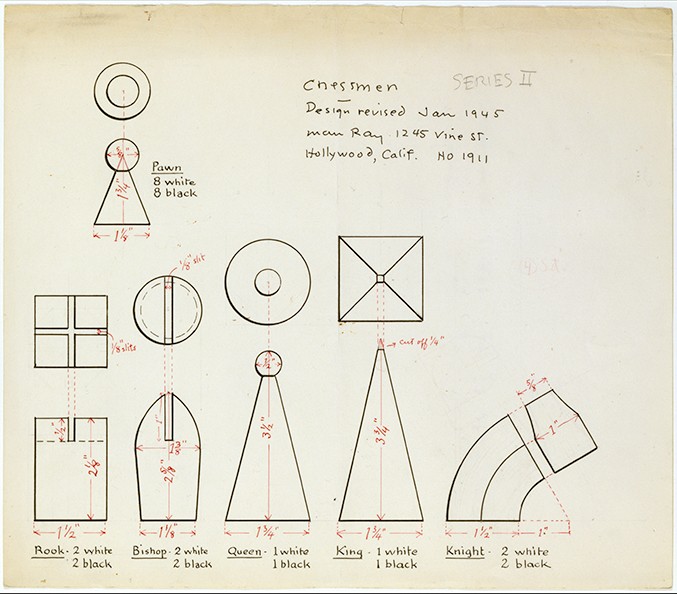

Man Ray

Designed by Man Ray (1890-1976)

American Chess Set, Designed 1944; made 1945 Natural and ebonized birch

King size: 3 1⁄2 in.

Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of John Harbeson, 1964

© Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2016

Designed by Man Ray (1890-1976), American

Chess Set with Board, Designed 1944; made 1945

Natural and ebonized birch

King size: 3 1⁄2 in.

Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of John Harbeson, 1964

© Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2016

The Surrealist artist and experimental photographer Man Ray contributed several works of art to The Imagery of Chess. As an enthusiastic chess player, Man Ray had been creating chess sets, as well as chess-themed paintings, drawings, and photographs, for decades prior to the 1944 exhibition at the Levy Gallery.

This particular set is a variation on the iconic set he designed between 1920 and 1924, which consisted of pieces inspired by basic geometric forms, including the cube, sphere, pyramid, and cone. He exhibited a modified version of the set shown here in The Imagery of Chess with pieces made of silver plate and oxidized silver-plated brass. Replicas of two of his preliminary drawings for his chess set designs are also on display in this exhibition. Following the exhibition, Man Ray created a limited edition of six of chess sets made of wood, which were signed and dated by the artist.

Man Ray (1890-1976), American

1962 Silver Chess Set and Table, 1962

Enameled metal chessboard with 32 Sterling Silver Players, Edition 1 of 5

King size: 3 1⁄2 in.

Table: 27 x 55 1⁄4 x 22 1⁄4 in.

Collection of Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield

© Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris 2016

This exquisite chess set and table was designed by Man Ray in 1962 and produced in Paris by Marcel Zerbib. The chessmen, similar in design to earlier versions of the artist’s chess sets with basic geometric shapes, are made of highly polished sterling silver and sit on an enameled metal chessboard that rests on a hardwood chess table. At the sides of each end of the table, hinged compartments store the pieces while not in play.

Delicately lining the border of the chessboard is a poem written by Man Ray:

le Roi est à moi

la Reine est la Tienne

la Tour Fait un four

le Fou est comme vous

le Cavalier déraille

le Pion fait l'espion

comme toute canaille

Fait de toutes pièces

(The King is mine

the Queen is yours

the Rook cooks

the Bishop reflects

the Knight is crooked

the Pawn spies

like all good rogues

he contains shades of the rest.)

Man Ray - 1962

Later, Man Ray went on to create and sell this same design in an edition of 50 with subtle variations.

Man Ray (1890-1976), American

Design for Chess Pieces, 1945

Reproduction of drawing

12 x 13 3⁄4 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, U.S.A. Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Image Source: Art Resource, NY © Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS)/ ADAGP, Paris 2016

Shown here are replicas of two drawings Man Ray may have exhibited in The Imagery of Chess. In the early 1920s, the artist designed a chess set for which the pieces were derived from basic geometric forms—the sphere, cube, cone, and pyramid. He later modified that design to create this version, which he went on to manufacture in a limited edition of six. The drawing Design for Chess Pieces shows his exquisite, sleek designs for his new set, an example of which is on display in this exhibition.

Man Ray (1890-1976), American

Recto: Perspective Study for Chess Pieces; Verso: Lithograph Published in a 'Book of Divers Writings', 1945

Reproduction of drawing

12 x 13 3⁄4 in.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, U.S.A.

Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Image Source: Art Resource, NY © Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS)/ ADAGP, Paris 2016

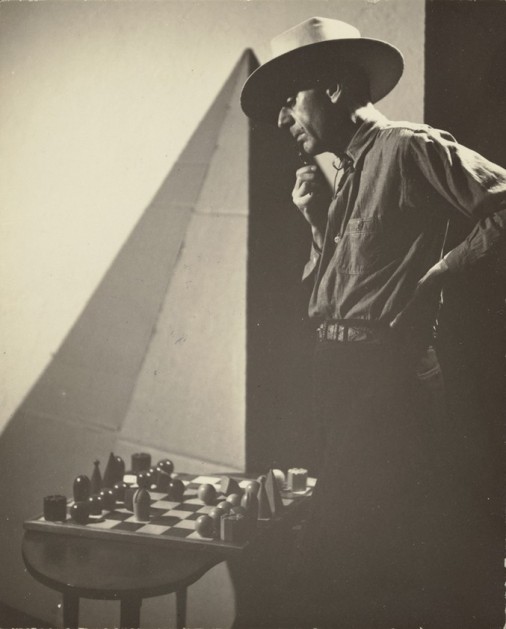

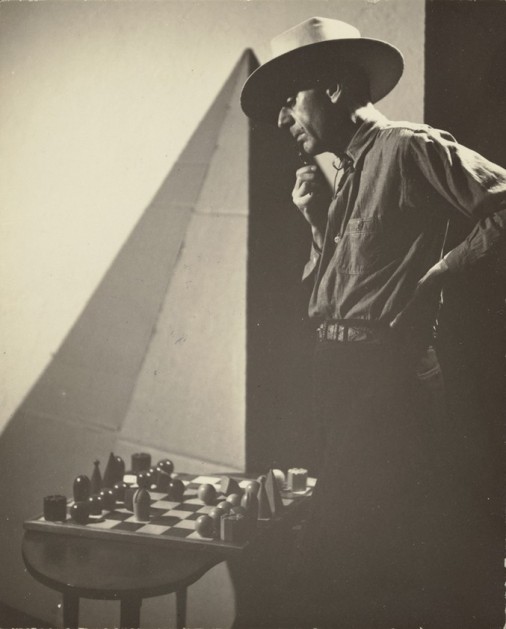

Man Ray (1890-1976), American

Self-Portrait with Chess Set, c. 1944

Reproduction of photograph

5 x 4 in.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Man Ray Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS)/ ADAGP, Paris 2016

Chess was a frequent theme in Man Ray’s work throughout his career, particularly in his photography. Due to work commitments in California during the winter of 1944-45, the artist was unable to travel to New York but contributed several works of art to the Levy Gallery exhibition. This photograph, dated 1944, may have been exhibited in The Imagery of Chess.

Tanning

Dorothea Tanning (1910-2012), American

Endgame, 1944

Reproduction of a painting

Private Collecction

Image Courtesy of the Dorothea Tanning Foundation © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

The painter, sculptor, writer, and poet Dorothea Tanning was one of the most prominent women artists of the Surrealist movement. Her phantasmic chessboard shows an endgame in which faint outlines of moves that only a queen could make lead the viewer’s eyes from the rooks in the upper right corner to a heeled shoe crushing a bishop’s miter. The serene, naturalistically painted landscape seen through a “rip” in the chessboard at the lower left contrasts with the violent and highly symbolic scene above.